If you walked into a room that Callum Turner was standing in, and you didn’t know he was a Hollywood actor, you’d be forgiven for thinking that he was a rower.

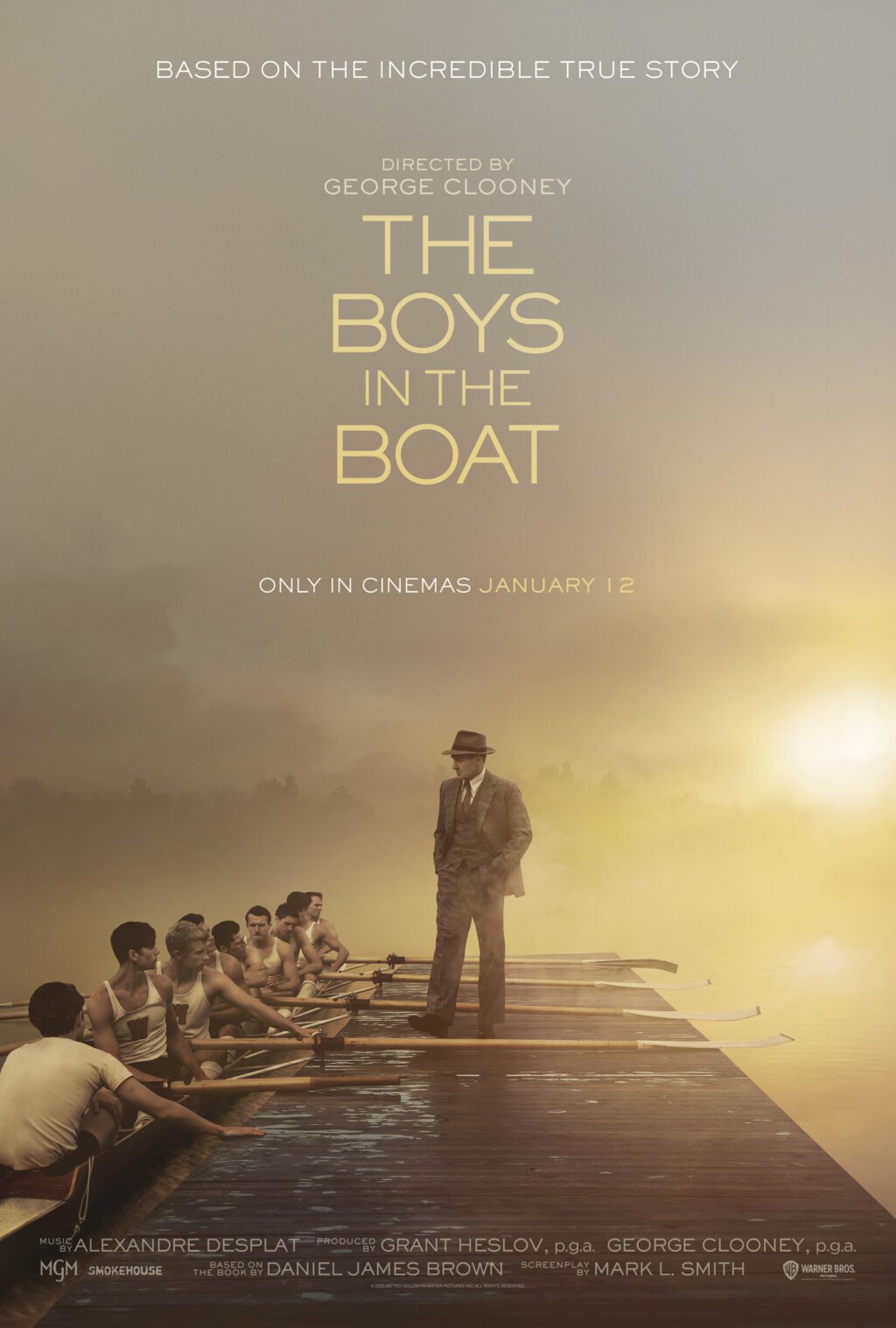

Meeting him for the first time, close to Embankment station, he towers over me in his pea green cardigan and white t-shirt. At six foot two, Turner is only an inch shorter than Joe Rantz, his character in The Boys in the Boat, a recently released drama which tells the story of the University of Washington’s men’s eight making it to the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games. No longer a bleach blonde, how he appears in the movie, I almost fail to recognise him.

Before filming commenced, Turner had never set foot in a racing shell, let alone taken a stroke. It had always been a dream of his to star in a sports film, but as a known Chelsea fan it was too easy to assume this might have been on a football pitch, instead of along a river. Rowing was something he’d have to learn from scratch.

“It was incredibly daunting. I remember being in a tank and thinking ‘this is pretty easy,’ and then we got into the boat. We went down to the Thames and it was freezing cold, snowing a little bit. I’m wrapped up and I’ve got these tight leggings on. And we were awful. We had no idea what we were doing.”

“I’ve got a special place in my heart for Joe Rantz. I adore the man. I cried when I first read that story.”

Callum Turner

It quickly became clear to George Clooney, sat in the director’s chair, that getting eight men who’d never rowed before up to a level at which they could convincingly recreate the victories of a national team would be no mean feat. Supported by a score of professional athletes, Turner and the other actors playing members of the medal-winning crew were made to train every day for two months before the cameras even arrived.

“They would sit between us,” Turner explains, “one of us, a rower, one of us, a rower. They would be able to coach us from behind, like ‘arms down’ or ‘off the foot plate’. That really helped. Because when there’s eight people who don’t know what they’re doing, there’s no one to be led by, even though you’re meant to be led by the stroke.”

“We probably had like 30 to 40 people from the rowing community with us at all times. And I think that they were so kind to us because they saw that we cared. It really mattered to us that the rowing was good. That’s a vital part of the film. If I watch a football film and I can see that they ain’t playing football properly, it takes me out of it.”

In charge of putting the team through their paces? Ex-Olympic rowing coach Terry O’Neill.

“Terry’s old school, to the point. He doesn’t beat around the bush. But he’s also one of the most charming blokes you’re ever gonna meet. He’s a real softie underneath, I’m sure. Maybe 20 years ago he was a lot tougher. We were so lucky to have those guys: Vicky [Thornley] and Nick [Harding] too, and all the others that were there.”

At a later stage in the training camp, O’Neill encouraged the actors to try sculling too, with mixed success.

“The sculling went well, yeah…” Turner begins, looking away from me for the first time.

“Doesn’t sound like it went well…” I hint.

He laughs brightly.

“Alright, I fell in… I fell in twice. I remember it was a horrible feeling because Jack [Mulhern] didn’t, and then everyone rowed back in the eight and they were all like ‘well done Jack!’ while I was soaking. It’s a different skill ultimately. I learned how to row in an eight and then learning to row a scull was like ‘okay, I need five months for this too’. And we were learning in wooden boats from the thirties. It wasn’t like we had the modern ones.”

Fortunately, when the time came to shoot the film’s epic race scenes, Turner and the rest of the guys pulled it off, but this hadn’t always seemed certain.

“There were moments where we weren’t sure if we were going to be able to do it. We would get into the fours and we’d be able to do it and then we’d go in the eights and it would be wonky or someone would be off balance or someone’s hand would be high.”

“Half-kidding, I ask if he’ll let me in on his erg scores. I’m surprised when he says yes.”

Ceci Browning

“There were a few days where I went home and was sat in the bath with all of the bath salts, watching Going For Gold, trying to recover,” he recalls, stretching out his long limbs as he imagines himself back into recovery. “And I remember thinking ‘I don’t know why I’m doing this.’ But I’m so glad that I did, because I loved every second.”

What strikes me most is that months after filming, Turner is still intensely curious about all the ins and outs of the sport. He wants to make sure he’s using the right language, to impress me with all the technical knowledge he’s got stored in his head.

“Do you call it single sculling?” he asks, propping up his face in one hand. “Or just sculling? I’ve got to get the jargon right. There’s no double sculling is there?”

I explain to him gently what a double scull is and he listens intently, blue eyes wide.

Despite the project being Turner’s first time with an oar in his hands, he reveals that he had come into initial contact with rowing a long time before.

“My first exposure was Redgrave – of course – the most famous Olympian from our country of all time. I remember as a kid, not having any knowledge about it, just knowing that he could win races. I was so inspired by him, his complete dedication to a practice. Watching him in the erg test against Pinsent. And the younger guy, the cooler guy, James Cracknell. Redgrave just blasted Cracknell, even though he’s like 20 years older. That guy’s a god.”

Once they had conquered all of the basics, Turner and his own crew mates also ended up battling it out to be the most powerful and have the best technique.

“The competitive nature of being a sports person is what’s exciting about it,” he says eagerly. “You’re pushing each other. Jack and I had probably like four arguments. Full on arguments in front of the crew. Because we really cared. That level of determination was the thing that pushed us to reach our target of rate 46. It might have only been for 45 seconds or whatever, but considering where we started, to get up to that was such an achievement for us.”

Half-kidding, I ask if he’ll let me in on his erg scores. I’m surprised when he says yes, insisting on finding his personal best from the depths of the cast group chat, imaginatively titled ‘THE boys in the boat.’ He scrolls through a huge backlog of WhatsApp messages as he talks, searching for photos of black digits on square screens.

“I really want to tell you the time. I was the best on the erg. I had the most amount of power off the foot plate, although I wasn’t the strongest.”

After a minute or so, he locates a score to report back to me. While it’s not the 2k time I was hoping for, it’s a number, at least. In Terry O’Neill’s legendary 4-minute test, Turner rowed 1189 metres. It’s not brilliant, but it’s not bad.

While the story is set mostly along the Western coast of the United States, the rowing scenes were primarily filmed on English waters. The first race of the movie was shot along the famous Henley stretch, kitted out to look like Washington. This, for Turner, was a highlight, getting to stay for a while in such a picturesque corner of the country.

“Oh, my God, it’s so beautiful. I love it. I loved Marlow, I loved Henley, and then we sort of bounced down to the Cotswolds too. It’s just really beautiful part of the world.”

Production itself wasn’t easy. Faced with the tricky task of capturing fast-moving scenes on the water, Producer Grant Heslov had to be methodical in his planning.

“We shot with five cameras,” Turner shares. “George describes it as being ‘a math’, an equation to work out. There are things that go wrong. Boats float and move where they shouldn’t go. It’s a three metre, four metre, boat and the oars are long, so you can’t get everyone close together to get into one shot. But I think George and Grant really did an incredible job for us. We were just stressing about the rowing. I’ve always had tunnel vision. It’s not my job to worry about where the cameras are. I just gotta focus on not being the one that catches a crab.”

“Redgrave just blasted Cracknell, even though he’s like 20 years older. That guy’s a god.”

Callum Turner

The film is based on a book of the same name by Daniel James Brown, who met original crew member Joe Rantz and heard firsthand the incredible true story of his life. Aged fifteen, Rantz was abandoned by his family and left to raise himself, making it all the more remarkable that he went on to win gold at the Olympics. Turner emphasizes how important it was to do him justice.

“I’ve got a special place in my heart for Joe Rantz. I adore the man. I cried when I first read that story. It’s so heartbreaking and I felt responsible for him as a character, as a person, and his legacy as a real human being.”

But perhaps the most rewarding part of the entire project, Turner suggests, was his acceptance into the world of rowing by the people who know it best.

“I was at a dinner recently with a bunch of famous people and there was someone who came up to ask for my photo because he knew that I was in this film. He didn’t want anyone else’s photo. He was like, ‘you’re the rower guy!’ I really love being part of this community.”

Now, he confesses, it feels as though he’s finally scratched his sporting itch.

“Those five months of my life are the closest thing I’ll ever have to experiencing being part of a professional sports team. We had physios and nutritionists and PTs and coaches. And a target. I think it’s like love, you know, love needs a goal. You need to be working towards something together, right? It’s the same for a sports team. We had that target of 46, that’s what they set us. It was difficult and arduous but fulfilling and rewarding and euphoric.”

Just before we say goodbye, I ask Turner how long it took for his hands to recover after filming had finished. He holds his huge blister-free palms up to me, grinning.

“About six months.”

Listen to cox Bob Moch recall his experience of the 1936 Olympic final.