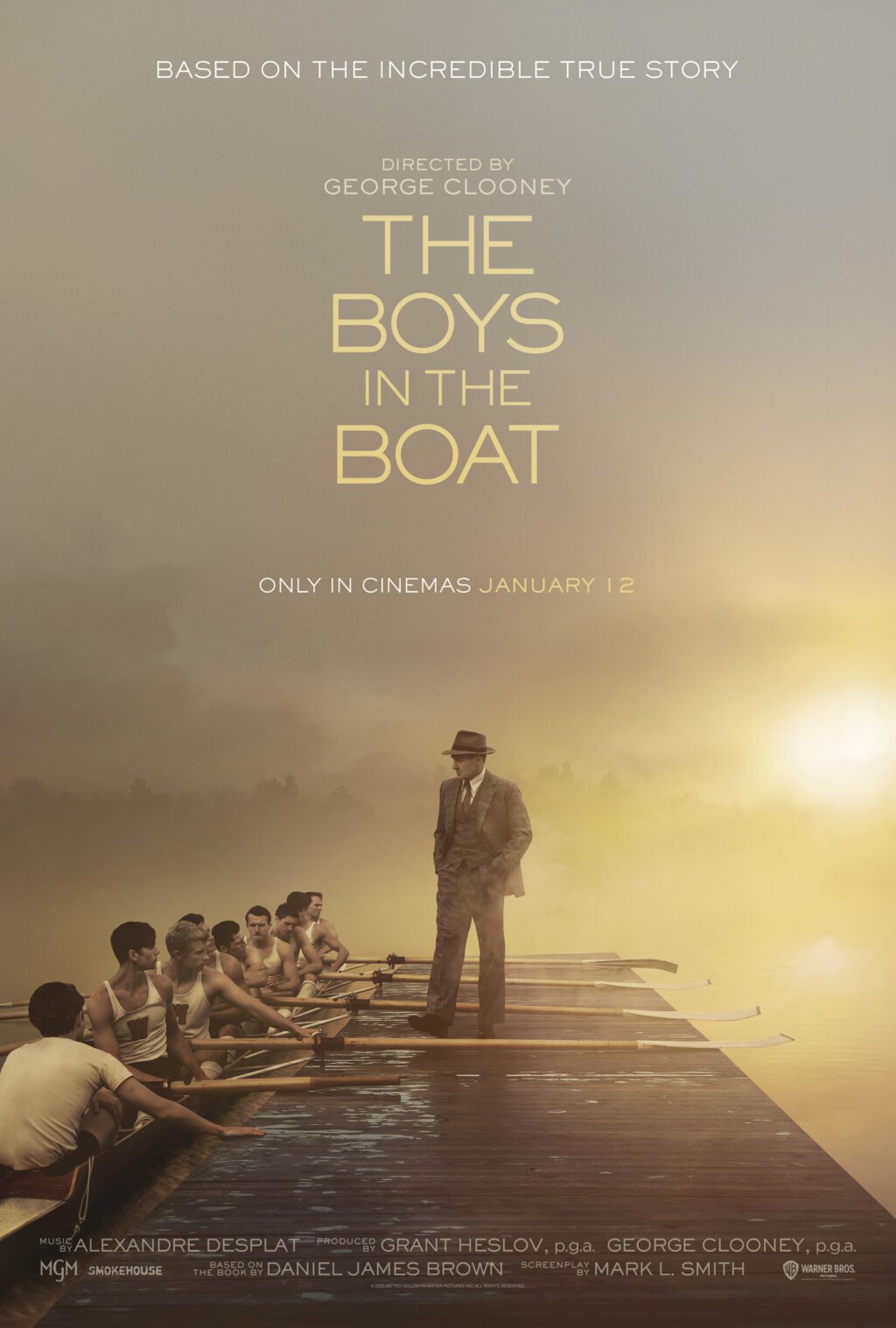

Great cinema creates a timeless bubble in which to float away and lose yourself for an hour or two. To inhabit this make-believe world, movie-magic must fashion a hook on which to catch and pull you through the film. Think, plot; visuals; sumptuous characters or a stellar score. If a film levels up on all four, even better. For me, The Boys in the Boat just misses the mark. The plot is decent but familiar, the visuals are strong as are the characters, but nothing grabbed me. I never felt a true sense of peril or excitement. Pappy in places, the whole thing ticked along like an above-average row: good but not good enough. And Coach, do we really need another film aggrandising silent, moody, males who don’t like to smile and struggle to express their emotions? (Also, with only two significant female characters it almost certainly fails the Bechdel test. But, perhaps, that’s too much to ask of a rowing film set in 1930s America.)

Let’s start at the start. The films opens with an older gent, peeling an apple at the riverside looking out at modern-day rowers paddling upstream, some boys in an eight and a youngster in a single. The apparent, impending jeopardy comes from the wash created by a raucous group cruising in a speedboat. It all feels painfully innocent: a throwback, vanilla-vibe from yester-year, ‘straight to DVD’ old-fashioned family hits from the ‘90s, ready to rent at Blockbuster. The older gent is Joe Rantz, and the film returns to this scene after telling the story of Rantz’s 1936 USA Olympic crew.

For me, the best scenes are in the boathouse and the training environments. The rowing itself is of a decent quality and doesn’t detract from the story. The handiwork of the actors and those who taught them to row pays off. The texture and feel of the ASUW boathouse, despite being a replica, comes alive, as does George Pocock’s (Peter Guinness) workshop. Likewise, the sense of being in a boat club, training together, and forging a team spirit (a central theme of the film) is captured well by Clooney. And the audience response – at least the one I watched it with echoes this: laughs bookended the training montage: first, when Joe (Callum Turner) and his classmate-cum-teammate Roger Morris (Sam Strike) realise who they’re up against on the first day of practice, and afterwards, hobbling back into class. DOMS (delayed-onset-muscle-soreness) gags relate no matter the era, apparently.

The cast produce a solid performance, most notably from Turner and Jack Mulhern the latter of whom plays strokeman Don Hume. Composer Alexandre Desplat scores the film expertly, marrying the metronomic rhythm in the boat with suitably triumphant orchestral numbers. Previous to this film he worked with Clooney on four others, including the political thriller The Ides of March, and in 2023 scored Netflix’s sports-drama Nyad.

Underdog sports movies walk a well-worn path: the underdog ultimately prevails. For this reason, it is key that the audience lives and breathes their hero’s journey and truly buys-in to the characters. For it to be a good watch they have to be emotionally invested, there needs to be something at stake. (Clooney revealed Survive and Advance, ESPN’s sports-doc based on NCAA basketball, provided a non-rowing source of inspiration.) Reading The Boys in the Boat I was absolutely emotionally invested and, despite the dense, research-backed writing I was thirsty for more after turning the last page, trawling online for vintage Pathé newsreels. That wasn’t the case when the credits rolled. Why didn’t I care as much?

Read our interview with British actor Callum Turner, who plays Joe Rantz.

Mark L. Smith, who wrote the screenplay, described the original book by Daniel James Brown’s as “sprawling”. He ruthlessly chopped context, backstory, subplot, and peripheral characters, to shrink the film’s central timeline to one year. Pruning the original book – where readers learnt for example about an all-time record leap in the stock market (15.34 per cent in one day), a bonus the filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl received from the Nazi’s chief propagandist Joseph Goebbels for her film Olympia (100,000 ℛℳ), and the University of Washington’s football team’s winning streak from 1907 to 1917 (63 consecutive wins) – was necessary, but the full-force of the story is diminished.

“I like to do cynical films. I like challenging people: Pissing people off. … If I’m allowed to play in the sandbox then I might as well try some stuff. This felt like none of those things.” Clooney said on the promotion trail, via podcast. “We’ve all been worked over the last few years, in life – sort of in the whole world. I feel like people have been separated into one side or another and gotten angrier and angrier and angrier … when I read the book I was inspired by the idea that we can’t do this without one and another, you can’t get through it without one and another. And that’s the feeling you got from these kids that were torn by the Depression and forced together and ended up somehow being George, John, Paul and Ringo.”

If the objective is to deliver a harmless, non-challenging film with zero bite then the dramatic structure and payoff has to land perfectly. It didn’t. It’s far from a damp squib but still more of a washout than a knockout.

“A perfect post-training flick for wet, cold Sunday afternoons.”

Tom Ransley

One of the biggest challenges Clooney faced was to make rowing look exciting on the big screen. It’s a sport obsessed with delayed gratification, repetition, and teamwork. There are no flashy stars and seldom does the big moment reveal itself in a cinematic, in-your-face kind of a way.

“It’s not the most exciting sport. It looks slow,” said Clooney, after shooting the film. His trick was to pack the big races with a succession of quick cutaway shots and edits, approximately 600 for the Olympic final. And for added dynamism and zip, Clooney “tried to get in tight enough [and] move the camera a lot”. There were a lot of push-zooms into the crowds, coaches, and Joe’s sweetheart Joyce Simdars (Hadley Robinson) by the radio, listening from home. The close-up, low angle shots of cox Bobby Moch (Luke Slattery), who had some lively dialogue (typical cox!), worked well. Fast moving shots that went counter to the direction of the boat, flying above the crew as they rowed towards the viewer, were also exciting, but by the third and final big race, it felt weary and a little thin, like a New Year’s fireworks show that just needs to end.

The final scene returns to the present day. As the sun sets on a rural backdrop, elderly Joe imparts words of wisdom to his grandson, the young sculler pushed into the reeds by the wake of the speed boat. It has more than a whiff of, “and it was all a dream…”. Was there not a better way to open and close this movie? I left the cinema with a sinking feeling. I wanted to love it – I really did – rowing writ large on the silver screen, what could be better?

Hammy, syrup-sweet family-fodder with side order of cheese, please: Spielberg-esque for not quite the right reasons. Still watchable, a perfect post-training flick for wet, cold Sunday afternoons. Three out of five. On a good day. The real story is better than the movie, and I wish I could have given it seven out of eight.