Christopher Dodd on the FISA president who fought the good fight in the Olympic arena.

It is more than 30 years since the death of Thomi Keller. Three generations of rowers have thus grown up without experiencing the powerful oratory, wry humour, rasping admonishment or whooping joy from the towpath of a president who for more than thirty years led rowing, its international federation and, arguably, the Olympic Games to a better place.

Photo Thomi Keller with Stuart Mackenzie (left), 1959

Born into a well-to-do Swiss family on Christmas Eve 1924, Thomi became fatherless when he was six. His father Max was tragically killed by a lion while hunting near his sisal farm in Tanganyika (now Tanzania). The family settled in a former restaurant on a hillside overlooking the Zurichsee. Thomi tried football before becoming an accomplished ski-jumper and cross country skier, and then in 1940 began sculling at Zurich’s Grasshopper Club, the start of a career that made him national champion and bronze medallist in the European championships in 1950. He studied chemical engineering at Zurich’s Polytechnic, married Dorry Bodmer, and in the early 1950s did a stint in the Keller trading house in Hong Kong and Manila. When he returned to Switzerland in 1954, he set his sites on sculling in the 1956 Melbourne Olympics.

Melbourne turned out to be the first of three game-changing events in Thomi’s life that were beyond his control. Shortly before departing for Australia, the Swiss oarsmen and participants in most other disciplines were pulled out of the Games in protest against the Soviet Union’s tank-driven crushing of the anti-Communist uprising in Hungary. The Swiss athletes argued in vain that withdrawal was not an appropriate way to protest against Russian aggression. Thomi was a signatory to the appeal to the Swiss Olympic Committee and became a prominent member of the ‘Melbourne Club’ of deprived athletes and the aircrew who would have flown them to the Games. The gymnasts who had favoured the boycott were not invited to the club’s get-togethers.

Thus began Olympic boycotts, and thus Thomi Keller lost his last chance to represent his country at the Games – and was poised to campaign against politics interfering in sport. Indeed, there were already quite enough political issues in sport itself for the pitch to be queered by world affairs.

Two years later, he and his sculling partner Hans Frohofer were presented with medals by Gaston Müllegg at the international rowing federation FISA’s Founders’ Regatta. Six weeks hence 68-year-old Müllegg was killed when the light aircraft he was flying crashed near the IOC’s Lausanne HQ. Gully Nickalls wrote his obituary for the Times, describing him as tall and spare figure who had given FISA unity and ‘endowed it with a presence and importance in the counsels of world sport which it had never previously enjoyed’.

This was in 1958, an era when the prevailing ambience of sport was traditional, amateur and conservative, and nourished by the amateur gentlefolk who mostly ran it. Although blessed with an able president, the rowing federation was no exception. Founded in 1882 – before the modern Olympics – FISA was largely a European club until well after the Second World War. The USA was the only English-speaking federation that signed up before the war, and there were virtually no members from Asia, Africa, or South America.

So it came as an eye-opener when Thomi Keller, a 33-year-old active oarsman, was elected to the presidency at a special congress in Vienna later that year. He was unopposed at the last minute when vice-president Jacques Spreux withdrew his nomination. With Thomi in the chair, things would soon begin to jump. He had not appeared entirely out of the blue, however, for Müllegg had identified Keller as his successor when planning his retirement in 1962.

Photo Thomi Keller accepts presidency of FISA in Vienna, 1959

The third game-changing episode concerned the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the quest for a successor to its president Avery Brundage. Late in 1968 the death of Swiss IOC member Albert Mayer created a once-in-a-lifetime vacancy on the Olympic body. Brundage, hanging onto office in his eighties, sounded out Thomi for the position. But in the back of the American’s mind may have been the notion of the Swiss rower succeeding to the presidency.

What Keller and Brundage shared was distaste for commercialism, the demands of television and sponsorship that were threatening the old order. But the distaste was about the only thing they shared. Apart from a significant programme of reform and modernisation in rowing, Thomi had been instrumental in setting up GAIF, the association of summer Olympic sports, which was making demands on the IOC – which was itself creaking under funding problems, disagreements over defining who should be allowed to take part, and fractious relationships with national Olympic committees (NOCs).

Thomi was in a dilemma, no question. He told Brundage in a roundabout way that his financial and business position would enable him to volunteer as IOC president. But the rest of his reply to the IOC president sounded an abrasive tone. It’s neither correct nor advisable, he said, to be an IOC member and president of an international sports federation at the same time. He planned another ten years in that role at FISA. He was hoping to be elected president of GAIF. Therefore, only if he could see a way of serving the ideals of sport as he had done heretofore would he be prepared to abandon the FISA presidency. Membership of the IOC, he said, does not seem to entertain this idea, and he would only consider it if there was the possibility of becoming Brundage’s successor. Nevertheless, he concluded, the duties connected with the presidency and the opportunities to serve our ideals to influence the future of sports ‘tempts me very much’.

Before Raymond Gafner had been sworn in as the new IOC member for Switzerland, Thomi was elected president of GAIF, consolidating his position as one of the most powerful men in world sport, but closing the door to the IOC and the Brundage succession.

When elected to head FISA in 1958, the new president had immediately set about reform and re-thinking where his sport was and where it was going. He visited regatta sites and agitated for improvement of facilities, being particularly anxious about the course set in the ‘floating gardens’ and canals of Xochimilco for the Mexico Games of 1968. It was, typically, way behind schedule, but opened on time as a superb, man-made, facility. The Rome regatta in 1960 took place on the round lake of Albano, overlooked by Castel Gandolfo, the Pope’s summer palace. Six straight lanes of 2000 metres were laid out by attaching red and white buoys to submerged cables linked to piles at either end. The Albano system became a FISA standard. Tokyo set out in 1964 with no piece of water wider than four lanes. The Toda course that was eventually used had problems with fair conditions, and some finals were delayed until they had to be rowed in the dark, illuminated by flares and car headlamps.

Photo Thomi Keller arriving at Henley in 1955.

Other issues of immediate concern to Thomi and the FISA volunteers whom he recruited with careful scrutiny were travel time betwixt Olympic villages and rowing lakes, the standard of umpiring and the cost of equipment. Through all these issues and their reforms, the quality that Thomi sought most was fairness. Crews should have as level playing water as was possible for an outdoor sport that was a bedrock, founding sport of the modern Olympics – and a sport that must grasp expansive universality if it was to remain in that essential place.

In 1972 the Irish peer and former oarsman Lord Killanin succeeded Brundage as president of the IOC. From his power point at GAIF Keller was opening the IOC’s eyes to the increasing power – in a new world of agents, sponsors and broadcasting rights – of both the international sports federations and the national Olympic committees. He ventured into the business of sport himself when he became president of Swiss Timing, a marketing organisation to promote the Swiss watch industry and bid for lucrative timing contracts for the Olympics.

It was also Thomi’s strong belief that the federations, rather than the IOC, should be in charge of regulating their disciplines. The IOC’s role was to foster the ‘Olympic Family’ by, among other things, hosting periodic congresses with the feds and the NOCs.

At just such an event next year in Varna, Bulgaria, Thomi fired a broadside. In a 3,000-word address on the future of the Olympic movement he ranged over qualifications for taking part, the programme, the ceremonial, Juvenal’s well-known mantra ‘the goal should be a sound mind in a sound body’, responsibilities of the federations and leadership, among others. He flung down a gauntlet to the IOC that was picked up by the international press: ‘either the IOC must ally itself with modern competitive sport and be ready to face the full consequences, or the IOC must decide to limit the Games to genuine amateurs as Coubertin had originally intended and to make the necessary adaptations.’

A year previously, the Munich Games were marred by the Black September terrorist attack on the Israeli team. Then Mayor Drapeau’s Montreal Games of 1976 lost a lot of money, the Moscow Games of 1980 were heavily boycotted, and the Los Angeles Games of 1984 also fell victim of boycott but made a profit. Killanin had his hands full and resigned in 1980 to be succeeded by the Spanish banker and diplomat Juan Antonio Samaranch.

Photo Thomi Keller with Hans Frohofer and Thomi’s son Dominik

Thomi was at his strongest in the 1970s. For one thing, the introduction of events for women at the Olympic regatta in 1976 made rowing, albeit briefly, the sport with the most Olympic medals. This was a mixed blessing. In rowing and the Games, the Cold War generated medal table battles between the US and the USSR, East Germany and the USSR, and West and East Germany (to the annoyance of the IOC, who disapproved of competitive tables). A small sport offering many medals meant that throwing money at it was a no-brainer for Eastern bloc countries. Rowing’s high number of athletes fielded by a relatively small international federation brought increasing pressure to reduce numbers, which happened eventually when quotas were allocated after the 1992 Barcelona Games.

The coming of Samaranch turned the tide of power in sport against Thomi. The two most powerful men in the Olympic movement did not get along, and while Samaranch set about reforming the IOC, Thomi and GAIF were undermined by Samaranch’s ally, the controversial Italian, Primo Nebiolo, who secured the presidency of both the powerful International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) and the Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF, formed in 1983).

Meanwhile, Thomi devoted his last decade to taking rowing to new heights. Under his guidance the federation strove, successfully, to increase its member states outside Europe through its innovative development programme (including the proliferation of rowing for lightweights), promote good coaching, increase its voluntary commissions and professionalise its secretariat, enact fair procedures in selection and competition, lead the world in out-of-competition dope testing, and generally expand the measures laid down in Thomi’s famous ‘cook book’.

His diplomatic approach to potential Cold War arguments saved, for example, South Africa being thrown out of FISA during the apartheid years. He distributed power by appointing three vice-presidents (one from Monaco, one from the USSR, and one from West Germany) and ensured that East Europeans occupied some influential seats on FISA commissions. He abolished the flying of flags and playing of national anthems at world championships and successfully resisted their re-instatement during his lifetime – a life that ended just before the collapse of the Berlin Wall.

These comings and goings of the power struggle and the politics of international sport are set out in a welcome biography of Thomi by David Owen and commissioned by Thomi’s son Dominik. Owen says in his preface that ‘it is high time… an account was written of the very considerable part played by Keller in enabling sport to make a successful transition from the political era in which he cut his teeth as a high-ranking administrator to the commercial era with which … he felt increasingly ill at ease in his later years.’

Hear hear to that, and Owen goes on to say that ‘that it has fallen to me, a non-rower who never met Keller, to do this is, I’m afraid, just one of those things. I hope those of you who did know him will feel I have done him justice.’

Owen has, as befits a writer who is a former sports editor of the Financial Times and a distinguished blogger on the Inside The Games website, made a good fist of unravelling a fascinating life wrapped in complicated story in ‘Thomi Keller, A Life In Sport’. All that it lacks, inevitably, is some of the frisson that electrifies the atmosphere when Thomi was about.

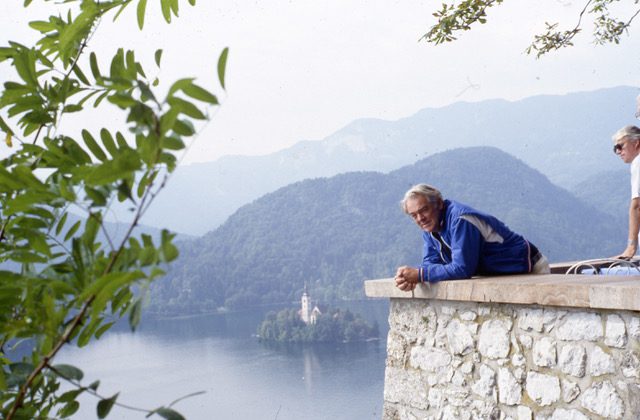

Photo Thomi at Bled, 1989

Credit Tina Fisher Cunningham

Throughout his thirty years in office, Thomi Keller’s voice was heard – in German, French, English, Spanish and more – and his presence was felt. He was a handsome man who carried authority and did not suffer fools. But he harboured no arrogance, was not toffee-nosed as some in rowing. He was a good listener, especially to his mostly handpicked coterie of experts and to athletes, hundreds of whom he knew by name. He could hold his drink in small-hours binges, had a sense of humour and treated everybody with courtesy and attention whether kings or commoners.

I first came to know him as a journalist, a breed that he understood from his days as a sportsman. I became a member of FISA’s new media commission when Thomi called a dozen people to a meeting in Frankfurt to canvas ideas. On the train to Germany I jotted down some proposals, one of which was to abolish FISA’s glossy and expensive-looking annual report that consisted mainly of an inventory of officials’ attendances at receptions and dinners during the year before last. I thought that my small bombshell would scupper any further role, but Thomi virtually signed me up there and then, and some months later, World Rowing magazine was born – in those days, on paper.

Thomi was a man who filled a room simply by entering, but he was humble in other people’s fiefdoms. He relished being a Steward of Henley Royal Regatta, umpiring races when called upon but not calling the shots (except on one occasion when a helicopter disrupted the start of a race and umpire Keller walkie-talkied Regatta Control to ‘have it shot down’).

In 1989 when he was struggling with the concept of retirement, Thomi made several visits to England. I was his guide and chauffer when he came to London to see the Boat Race live for the first time. At Henley we met again, this time on the Stewards’ sunny private lawn, where Thomi commissioned me to write ‘The Story of World Rowing’ as his farewell present to his beloved sport. The regatta celebrated its 150th birthday later that year by throwing a reception for all living winners of the Diamond Sculls. It also turned on a sensational climax when Notts County’s lightweights smashed Harvard’s until then unbeaten heavies and the record in a re-row of the Ladies’ Plate.

Later in the year at the world championships in Bled I began to gather Keller gems as we enjoyed a drone’s view of racing from high on the castle terrace. I was looking forward to sharing his company in the coming months. But alas, Thomi died a month later in Monte Carlo just as I was about to start writing. The book never had the benefit of the presidential horse’s mouth.

In his outstanding eulogy to Thomi at St Peter’s church in Zurich on 6 October, Peter Coni said ‘no other sport has enjoyed such wisdom and such personal involvement from its president. In all that he did as president, he showed common sense, honesty and integrity.’ Writing in the Independent, Hugh Matheson described him as ‘the outstanding figure in the history of international rowing.’

This article first appeared in