In the dying strokes of his Olympic debut, at Tokyo 2020, Team GB’s Sholto Carnegie fell just short of his ambition of winning an Olympic medal. Now, less than nine months until the next Games, Carnegie is hoping to convert Tokyo misery into gold and glory at Paris.

Photo Sholto Carnegie

Credit Benedict Tufnell

In the movie “Building Jerusalem” international rugby superstar, Jonny Wilkinson, talks about his worldcup-winning dropkick that saw England lift the 2003 Rugby World Cup. He describes it as a moment of ‘pure bliss’ but one tinged by the reality that every second that passed would take him further away from that glorious dropkick moment, and away from the endless hours of training, team bonding and the actual process of searching for greatness.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not comparing my ability to row with Jonny’s legendary kicking prowess but what does resonate with me is his take on time and the fleeting nature of elite sport.

Going into this season I feel incredibly excited by the opportunities that lie ahead, but I’m aware that this could be my last year as a full-time, professional athlete. I’ve worked hard to build the right tools for the job. My skillset before Tokyo was strong -I’ve always had a positive approach to racing and that’s allowed me to reach a certain level – but looking back I can see gaps in my approach.

I came up short at Tokyo and the pain I felt led me to do a lot of soul-searching. In 2021, I stroked the British men’s four. We arrived at the Games as European champions, fully intent on continuing Great Britain’s golden legacy at the Olympics in this boat class. Ultimately, we finished fourth, having sat in second for most of the A-Final. In the days and months that followed, I felt like someone had ripped out my heart. I know that sounds dramatic, but I was totally invested. So much of my identity was tied up in rowing and in the outcome of that one single race. Afterwards, when I caught up with old friends, they’d always ask about the Olympic experience and say how proud they were of me: their words fell on deaf ears. All I felt was a sense of shame and a massive, missed opportunity. It was a tough one to swallow but that period of grieving helped shape my outlook and it taught me resilience. I often wonder, what if we had achieved success in Tokyo – would I have been pushed to change in the ways that I have?

“Motivated by these experiences I decided to set up my own venture, a U.S. university recruiting consultancy called Crew Connection.”

Sholto Carnegie

I recall one critical juncture in my thinking. It was during a run post-Tokyo, I thought: “Sholto, you have to decide how to respond to this situation. Do I call it a day, or keep going?” I returned home and wrote out two plans. Plan A, keep rowing but find a way to have a healthier approach to outcomes. Plan B, get a job and join the real world.

I chose Plan A.

So, what’s changed?

Firstly, I started working with a sports performance coach to help improve my mindset. I worked on simplifying my approach and steering my attention to what I could control rather than wasting energy and attention on what I couldn’t, yet still acknowledging those ‘uncontrollables’. The more I develop, as an athlete, the better I get at noticing when my focus drifts.

Secondly, to improve my consistency, I breakdown the day into different parts and try to deliver each to the best of my ability. In doing so, the outcomes tend to take care of themselves. As pressure situations arise, I don’t slip into autopilot like I used to, instead I embrace the pressure and double down on delivering the controllables.

Photo GBR M8+

Credit Benedict Tufnell

It is a gradual process of change, but it is working. Before, my approach to pressure would’ve been to stay calm, keep my head down and row as hard as possible. Now, I have much more clarity in the processes behind my actions and I see pressure as a good thing; it means I care deeply about the race. That’s not to say I don’t get nervous, I do, but I am there to ‘greet’ (not bury) the pre-race nerves and emotions, and harness their energy. This approach has helped me to improve my performances, and reach greater levels of fitness, compared to the previous Olympiad. I also made changes outside of the boat. Since Tokyo I’ve completed several internships and part-time work opportunities. These have helped my mental approach to rowing. When I was away from training, I was able to focus on something completely different, returning mentally refreshed and present. The process of starting at the bottom of a company ‘food chain’ was an exciting challenge; incidentally the process of tackling a totally new task made me simplify my approach when working on the more nuanced aspects of my rowing technique.

Motivated by these experiences I decided to set up my own venture, a U.S. university recruiting consultancy called Crew Connection. I started Crew Connection with my oldest friend, and fellow oarsman, Jack Gosden Kaye. Crew Connection is a U.S. college recruiting advisory service that helps young athletes on their journey to being recruited to top rowing universities. It has reminded me why I fell in love with rowing in the first place and gives me an appreciation of my own sporting journey; from learning to row in wooden boats at City of Oxford Rowing Club to challenging for Olympic glory.

Working with these aspiring athletes has allowed me to realize the parts of the process that have become so engrained in my habit that I almost began to take them for granted. Seeing these athletes progress and achieve their dreams is incredibly rewarding and motivates me to achieve my dreams.

In one way the size of my dream has doubled: this cycle I’ve moved from the four to the eight. I thoroughly enjoyed racing the four; the bond you make with your teammates is very intimate but the eight has always been my true love. There is something very special about this boat class. I got hooked on racing eights ever since my freshman year at Yale.

“Old friends would always ask about the Olympic experience and say how proud they were of me: their words fell on deaf ears. All I felt was a sense of shame and a massive, missed opportunity.”

Sholto Carnegie

The energy of nine people trying to move in perfect unison to make the boat go as fast as possible is incredibly rewarding, especially when you make it happen in big, high-pressure situations. I love the feeling of being part of a big machine, producing an outcome far greater than the sum of its parts. Bliss, for me, is when all eight athletes are moving in harmony with the shell and all nine minds thinking and acting as one.

The closest we’ve come so far to pure bliss in our eight was during the last pre-worlds camp in Avis, Portugal, we spent many miles gliding across mirror flat water stroke after stroke, engraining consistency, perfectly attuned to the boat. However, I’m conscious not to dress-up the life of a full-time athlete as all sunshine and rainbows, it’s not. There are very hard bits, and motivation levels wax and wane along the way.

Right now, writing this, I’m coming off the highs of retaining my world title in the men’s eights and a well-earned rest in Puglia, Italy. But quicker than you can say, ‘Negroni, per favore’, it’s ‘arrivederci’ to the summer break and I’m back at Caversham staring down the barrel of a long gruelling winter: repeated physical tests on the horizon.

I always find the start to the season the hardest. The key to success lies in delivering consistency and pushing on through the tough winter training, especially when days start and finish in the dark. It is during those first few weeks of training that I begin to summon the emotional energy necessary to fight for my Olympic seat.

From the outside, the life of a full-time athlete is amazing, and truth be told, when you break it down, we are incredibly lucky, but day-to-day this gets lost. Lost among the gloomy, cold mornings filled with monotonous mileage. Lost on the long drives north to Boston, Lincolnshire, where the team fight tooth and nail along five (windy) kilometers of featureless river beneath grey skies and cabbage fields. And lost on yet another soul-sapping erg, or better yet an erg test.

“Bliss, for me, is when all eight athletes are moving in harmony with the shell and all nine minds thinking and acting as one.”

Sholto Carnegie

These less than glamourous mainstays all pull me away from the simple fact that I am fortunate to have a job that means so much to me. I try to hold on to this fact when the fatigue builds, and the daylight hours shrink. I focus on it, and try to channel its energy, and the excitement and sense of purpose that it brings. Each time it drives me to become the best possible version of myself.

In the months, ahead we have a series of 2k erg tests, water trials in pairs and high-altitude training camps in Sierra Nevada, Spain, falling either side of Christmas. This is not unfamiliar territory for me, coming into this year I will be approaching my second Olympic Games but my third Olympic year (thanks to a double dose of Olympic selection stress caused by the global pandemic). Anyone who has completed an Olympic cycle knows the Olympic year hits different from the the rest. Athletes arrive knowing what’s on the line, amped up and ready to dial into a higher-level of focus and summon their best-ever efforts.

This year is all about managing my focus and facing up to the challenge of Olympic selection. As the final year begins, our team’s time together is coming to a close. Every Olympic cycle is different filled with new personalities and characters.

It has been a real pleasure to be a part of the group that we currently have at Caversham; it balances a fine blend of fun, fierce competition, and having each other’s back.

People ask me how I feel going into this Olympic year and truth be told it’s mixed. I’m excited by the prospect of Paris but, with a nod to Wilkinson’s words of wisdom, this year more than anything else I want to cherish the small moments and the often-overlooked steps along the way.

Click here for more information on Crew Connection

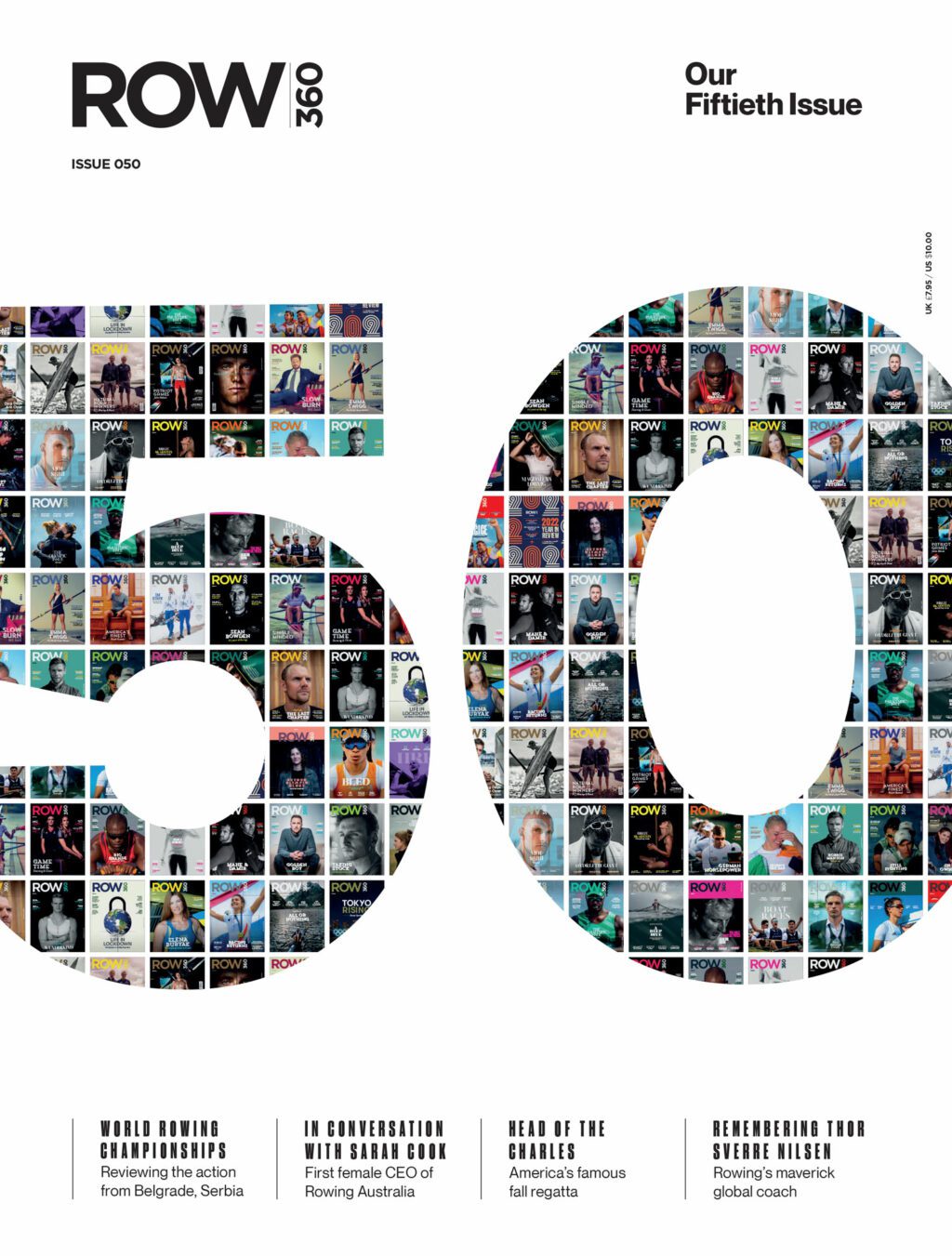

This article first appeared in Issue 50