Let’s say a country wants to send a rowing crew to the Paris 2024 Olympics or Paralympics. There is only a maximum of three chances for them to race to qualify: at this year’s worlds, at one of the special continental regattas, or at the last-chance races in Lucerne next year. The system, which has been in place since 1996 for the Olympics and for para-rowers since the 2008 inaugural Paralympic rowing regatta, hasn’t changed much this year, but it puts a huge pressure on those racing at the pre-Olympic worlds.

Qualifying at the first bite is enormously helpful. It cuts the need to artificially peak for a training-disrupting contest some time between October (for Africa) to May (the Final regatta). The earlier a team books their Paris seats, the more flexibility they have in their training programme. In addition at the worlds, it is the crew which qualifies, not the personnel, meaning that substitutions can be made and re-selection done to maximise medal-bagging chances. All the later events require the athletes who qualified to compete in that event, if they compete in any event at the Games.

For prospective Olympians, the opposite is true for those who qualify in the last-chance saloon of Lucerne’s May 2024 Final Olympic (FOQR) and Paralympic (FPQR) Qualification Regattas (this time jointly held). Those athletes are under a special extra burden: they must race with exactly the same personnel who took part in the FOQR, no changes at all. (That rule is not deemed necessary for the Paralympics where teams are much smaller and physical classification means seats can often only be filled by one person: spares are rarer.)

If any Olympic FOQR athletes are doubling up, they must race in at least that event at the Games: they can’t withdraw from their FOQR category then still race in their second boat class. The rules, designed to stop tactical withdrawals and abuse of the qualification privilege, also mean that if any athlete gets ill or injured in an FOQR crew, it can’t race at the Olympics. New Zealand’s men’s eight missed qualifying in 2019 by one place but pulled off the near-impossible two years later, reaching Tokyo by winning the FQOR, keeping the crew intact and then peaking again superbly to win the gold medal at the Games.

Over the years the numbers of slots available to each boat class at each stage have been tweaked to benefit World Rowing’s aims at the time. For Rio a lot of singles places were moved from worlds qualification to the continental regattas to increase diversity. Initially men had more Olympic qualification spaces at every regatta, reflecting the higher numbers of participants, but it was eventually realised that this simply held women’s rowing back. (Paralympic rowing was always completely gender-equal). Current IOC President Thomas Bach was elected in 2013, and his Agenda 2020 plan was adopted a year later, with gender equality one of its core principles. For Rio 2016 rowing still lagged behind this intention, with 331:219 men to women (total 550) but by Tokyo 2020 gender equality in rowing had been adopted with 263 athletes each, a total of 526 Olympic spaces, trimming numbers under IOC pressure.

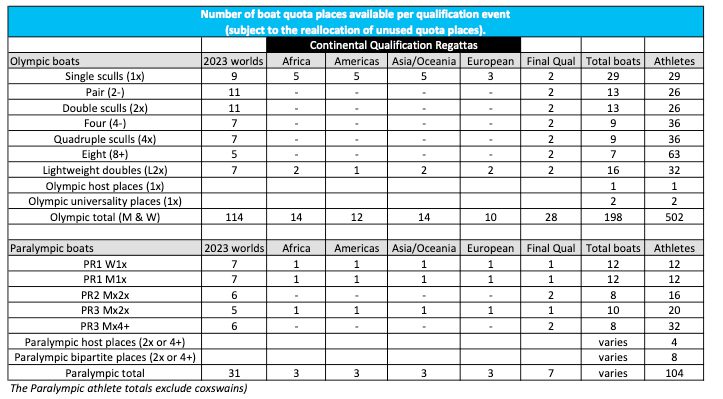

This year there has been another quiet squeeze on Olympic numbers, reducing the total to 502 athletes, shared equally between men and women. It’s all about the balance of medals, viewers and personnel: rowing has large teams (and a lot of ancillary staff) but provides only 14 gold medals and a limited viewing audience except for the finals. (Beach sprints, if agreed for LA2028, might provide a better cost-benefit ratio.)

Since Rio a large number of Olympic single and lightweight double places have been reserved for the continental qualification regattas. This continues for Paris, while the total number of fours and quads have been cut by one each, and there are fewer lightweight doubles than in Tokyo. All these constraints make the preceding worlds before a Games hyper-pressured.

Take the openweight pairs and doubles. They are large events with only eleven places on offer at the Belgrade worlds, so crews drop off the qualification pathway as soon as the repechages begin. Nerves continue through the semifinals, where six crews guarantee Paris spots by making the A-final, six more still have a chance, and the rest are out. The hottest races are the B-finals, where the only crew not to bag a place at the Olympics is the one who finishes last, i.e. 12th.

With no continental places, openweight pairs and doubles have only one option left after that: the Final Qualification Regatta, with all the difficulties that involves. Following New Zealand’s epic 2020 result however, countries may be more optimistic about this route than before.

Numbers are lower for fours and quads (seven worlds places) but the eights are even more brutal, with just five places offered in Belgrade. Before the medal race, the only thing known is who has already missed out by finishing too far back in the repechage or semi-final. In the A-final, the contest to come fifth is key. While the gold, silver and bronze medallists are celebrating, in the same race one crew will cross the line last and sit with heads bowed in misery.

The single sculls are where the broadest diversity qualify for the Olympics, but it’s also the boat class even the smallest rowing nations can try for. Of the 29 singles spaces on offer for each gender, only nine come at this year’s worlds and two at the FOQR. The other 18 can only be taken by countries at the continental regattas, and this is where there are some important extra rules.

Countries can only enter singles or lightweight doubles for their continental regatta if they have qualified one or fewer crews total at the previous worlds. This keeps the biggest rowing nations out of the regional regattas completely and stops them hogging all the Olympic spots. For those who didn’t enter the 2023 worlds, or entered but qualified none, they can qualify up to two crews continentally. For those with one qualified crew at the worlds, they can enter their continental event but qualify only one more crew.

Paralympic rowing has something very similar going on, with the PR1 singles and PR2 doubles being the continental events, although taking part in those is limited to countries which don’t yet have a Paralympic place and they can qualify only one crew there. Host nations without any other qualifications can get a singles place (Olympics) and up to one double or four (Paralympics) while there are always at least two universality or bipartite places for each gender, allocated jointly by the IOC or IPC, and World Rowing with the agreement of national committees.

It’s worth remembering that the IOC and IPC run their Games entirely independently, they aren’t a joint event. So qualification for the Olympics and Paralympics are completely separate even though we’ve combined them into one table. The IOC diversity places are called “universality” spots and are given to a small number of countries without any rowing representation at the Olympics. The IPC versions are called “bipartite” and allocate crew spaces to some of the countries without rowing representation at the Paralympics.

If the host nation doesn’t need its guaranteed places, or if any qualified crew withdraws before the Games or is unable to compete due to drug allegations or similar, then those places are reallocated by World Rowing in consultation with the IOC/IPC. This happened in 2016 when the exclusion of a large number of Russian rowers due to the McLaren report and the uncovering of the Sochi doping scandal led to their crew places being given to the countries who had finished just outside qualification at the FOQR and FPQR. It can all change until the very last minute. The most complex jigsaw in rowing is starting to assemble.