It’s Sunday 24th September 2017, and the Sarasota-Bradenton world championships are well under way. Standing on the vertiginous finish tower, looking out with satisfaction over the glistening lake and world-class facilities, radio in her hand, is arguably the most powerful woman in world rowing.

“Rio, I was so disappointed, we lost the grandstand on the water. Mayors (shrug) – they want to show they are stronger.”

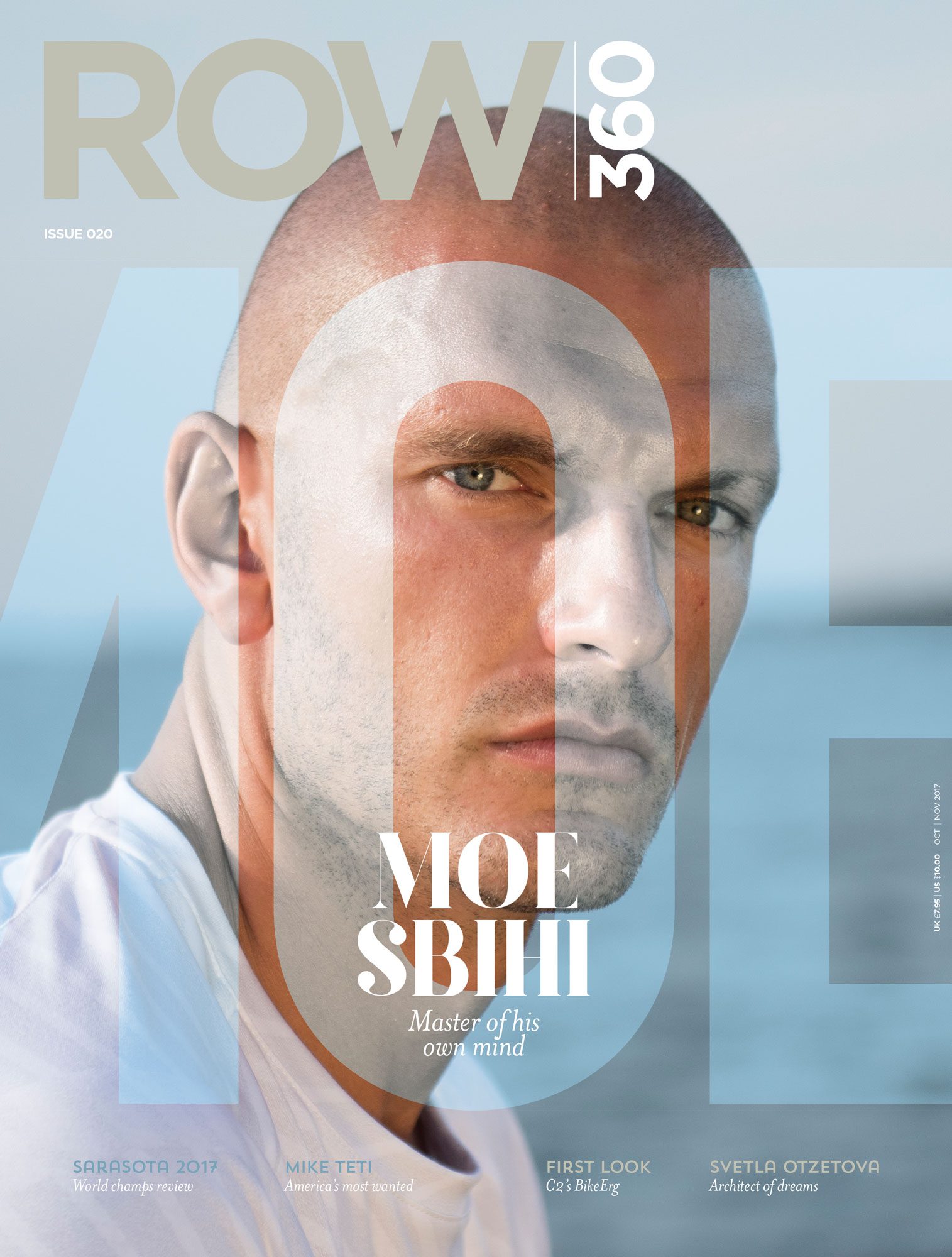

Svetla Otzetova

Svetlana Otzetova, FISA’s architect, course designer and logistics expert, is far from a show-off. A trim figure in her late 60s, Otzetova will talk for hours with enthusiasm about world rowing, but becomes suddenly shy when the conversation turns to her own career. Yet she is one of the greats, from the generation of Bulgarian rowers who made history for their country in the mid-1970s. And for 20 years she has not only designed new rowing courses, many of which have held world or Olympic regattas, but also refined and improved every practical detail of FISA events. She is rowing’s technical mastermind.

Otzetova, called ‘Svetla’, was born in November 1950, four years after the fledgling Bulgarian communist state was established behind the Iron Curtain. Initially drawn to swimming, she suffered unexpected illness. “I had a medical problem with my nose and ears, and I had to stop,” she explains. “The only sport that would take me at this age – far too late, 16 – was rowing.”

Living on Lake Pancherevo, near the capital Sofia, she tried the local rowing clubs. “I didn’t like it in the beginning, not at all. They put me in a four, it was so hard to turn the oars, I didn’t like it. But when we came off the water, the coach told us ‘next day, at this and this time, all here’. I was so modest and shy that I didn’t dare to say ‘actually, I don’t like it’. So I turned up the next time, then the next.”

“And one day one of my partners was not there, and so they put me in a single, it was March, and so we started rowing. I did one day, then the second, and on the third day, just when I had become self-confident and thought the world is mine, then I capsized.”

The untimely dunking did not put off the teenage Otzetova, who had discovered that she preferred being alone in a boat and was an excellent sculler. Five years later she made her international debut at the 1971 European Championships, at the time the most prestigious regatta for women, finishing fifth in a coxed quad.

The early seventies were a period of great change during which FISA moved from even years featuring either an Olympics or worlds (both men only) with dual-gender European championships in odd years, to an annual worlds starting 1974, involving both women and lightweight men. Olympic women’s events loomed on the near horizon: it was a great time to be an up-and-coming female sculler.

Otzetova’s crewmate in the middle of the 1971 quad was Zdravka Yordanova, with whom she created an exceptional partnership. In 1975 they tried the double, and promptly stormed the world. “A few weeks [after starting together] there was the big regatta in Moscow, with all the strongest nations in rowing — East Germany, Roumania, Russa,” says Otzetova. “We won, and it was a big surprise. That was the way it started.” A few weeks later they won bronze at the Nottingham worlds, joining three silver-medal crews as the first ever Bulgarians to reach the world rowing podium.

A year after that came the first-ever Olympic Games to include women’s rowing, Montreal 1976. Young guns Otzetova and Yordanova were packed off to Canada as part of a strong Bulgarian team. “And we won, nobody expected it,” says Otzetova, still sounding faintly surprised. They had a flying start, took three seconds lead, and never relinquished it. Bulgaria’s first ever Olympic rowing victory, along with the W2-. “We were surprised and proud, of course. We didn’t even realise how excited people were about it until we were back, then there was all the media attention. Rowing was big in Bulgaria at the time, very big. The team that went to the Olympics had 100 people, now we have 2, 3, 1.”

Otzetova and Yordanova continued together another Olympiad, winning the first ever Bulgarian world gold on her favourite Karapiro course in 1978, but meanwhile Svetla’s career beckoned. Technically-minded, she wanted to be an architect, and had studied engineering while waiting for a place. “I got a lot of the highest level of mathematics, and statics and so on. It’s been very helpful.” Finally she could transfer to architecture, which peaked at exactly the wrong time for her rowing.

“In 1976 I had to defend my diplome to become an architect. It was in May, a public defence, they asked lots of questions. I went through this and then two, three months later I was at the Olympics. It was really very tough, I remember that I was at the end of my nerves.” Studies followed her to every training camp.

“The team were not happy that I was sometimes not with them, because I had to work, to study. I carried around my desk — we did not have computers — so I had a big [portable] drawing table, and they gave me a small room in the basement to do my drawings. My [diploma] project was a sports facility: actually I had been planning at that time to be interested in the history of architecture. But you had to know facts, to make the sketches. I can’t remember names, and so there were other options, and sports [architecture] was one of them.”

That insignificant change in direction has moulded the whole of Otzetova’s life, as she started to take on small sports architectural projects she could achieve solo. From 1977 to 1980 she continued rowing too, then retired, had children, and worked for the Minister for Sport. Her first professional project was the 1980s revamp of Bulgaria’s Plovdiv rowing facilities. Meanwhile she was sucked rapidly into unpaid rowing work: attending the Olympic Congress in 1981 as one of the first athlete IOC members, then becoming vice-President and later President of the Bulgarian Rowing Federation. This gave her next big break.

“Otzetova’s clear-eye logic and appreciation of complex systems drags her into every aspect of FISA planning, from layouts of boathouses and racks to timing, transport, buses, electronics, the flow of athletes from lake to ergs to food tent.”

Rachel Quarrell

“I remember 1995 Tampere [worlds]. There was a visiting delegation — for the first time bidding cities [for the 2004 Olympics] were advised to ask directions from sports. The Stockholm bid committee were discussing plans, and the famous Thor Nilsson, who was a Council member at the time, he said “Why don’t you consult with Svetla, she is a trained architect.” So I was invited, and then I worked with them, this was my first Olympic bid project.”

In the end ten of the eleven 2004 bidding cities asked Otzetova to inspect their plans and courses. “I went to each of them, they put me sometimes in helicopters, I hate it — I don’t like heights — but I had to deal with it. Only St Petersburg didn’t invite me. Some places I had to go to twice, like Cape Town because they changed the venue.”

And with that, she was off, helping committees plan dozens of rowing lakes, sometimes over many years and even for failed bids. Right now she is in the middle of planning Tokyo 2020, and it won’t be long before her expertise is needed by Paris and Los Angeles.

Intriguingly her views have changed over the decades, as she moves from the drawing board to seeing a course work in reality. The particular bug-bear is wind, that complex combination of water, lake profile, wind direction and strength, which can lead to anything from record conditions to unrowable waves. Earlier in her career Otzetova aligned courses with a tail-wind, but now she is more cautious. “For example, when I was working on Athens, it is much in line with the wind direction, which I thought back then was the best. But the waves built up and up.”

The 2003 junior finals on the Athens course were famously cut to 1000m and held at 4am as a result of the boat-swamping waves in the second half, but wind alignment ideas persisted for a while, the alternative (hefty and unfair crosswinds) seeming less useful. Now Otzetova prefers a cross-wind, but with wave mitigation, and carefully graded banks to avoid wind shadow. “First thing I advise is always keep the bank as low as possible — a small drop to the water. Unfortunately in Eton they put some of the excavated material onto the land. Because of this bank — about 1.5m high — the wind comes in and hits the water. If you have a high bank you need to have it further back. Here in Sarasota the lake road [for TV cars] is very flat to the water, while on the far side although there’s a big drop, it’s a long way away from the side of the racing lanes. So the wind hits the water flat, you don’t get unfairness.”

“The Bosbaan [Amsterdam] has the forest, which keeps the wind away most of the time. But then if it’s blowing for too long periods of time in one direction, it starts creating waves. We always use meteorologists, we need to know pretty accurately what’s going to happen.” The soil type matters — soft earth prevents steep lake walls being built — good for wind but not always forgiving on space. In Amsterdam she came up with a solution allowing the creation of shallower banks without narrowing the lake. “In the Bosbaan we made partly a slope and then dropping vertical below the water level, from about one metre below. Gravel and sand are good: in Sydney they also planted some reeds, which look nice and cut wash a lot.”

Tokyo 2020’s particular issue is the course’s wash-bouncing vertical walls. “In Tokyo they are installing wavebreakers, supposed to absorb the waves. If they don’t work, we make new ones, we are still discussing material and shape.” Otzetova nowadays gets organisers to spend money on proper computer modelling of wave and wind effects, especially at the lake edges. The bane of her life is mayors, particularly of Olympic cities, who tend to show off in local politics at the expense of her careful plans. “Rio, I was so disappointed, we lost the grandstand on the water. Mayors (shrug) – they want to show they are stronger.”

Otzetova’s clear-eye logic and appreciation of complex systems drags her into every aspect of FISA planning, from layouts of boathouses and racks to timing, transport, buses, electronics, the flow of athletes from lake to ergs to food tent. She works closely with timing sponsors Omega, who brought in the GPS bow-numbers, and have now moved to automatic camera split-timing at FISA events, so that volunteers need not sit in draughty high towers at each 500 marker. What were her views on the 2016 M1x photofinish? She looks coy. “Hmmmm. No, I must keep my mouth shut until we have a new rule. It’s not ready yet, but I will tell you when it is.”

Youthful as Otzetova is in attitude and outlook, she is considering retirement. FISA will need to replace her with at least two others, and in Sarasota a different FISA employee took over the regatta’s on-site logistics. “Because I combine technical, venue layout, organisational, administrative, what I’m not trying to do any more is administration. I’m trying to pass on as much information as possible to the younger ones. I will do Tokyo if they want me, but for sure I do less now.” It’s giving her months at home, spending time with masters rowing friends, hiking and climbing, an outdoors life. “Because I’m living on Poncharevo, maybe I’ll start rowing again. I’m looking forward to having more time.”

And at Sarasota, there was a little surprise in store for her. “The third day when I was here, one of the officials came and…

Full article available in Issue 20